Editor’s Note: In our ongoing coverage of cockroach allergens, the July issue of PCT will feature a story by University of Florida doctoral candidate Julieta Brambila, covering the topic of cockroach allergies and asthma.

PCOs have sought for years to educate customers that cockroaches are more than simply disagreeable to the eye; that they also spread filth and disease. But now this pest has been implicated in an even more serious and life-threatening ailment: childhood asthma.

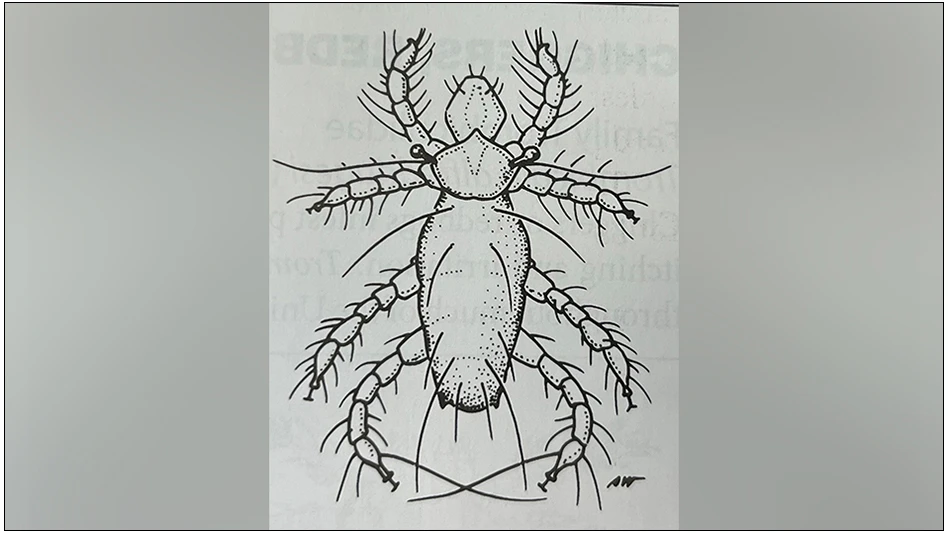

According to a major study, details of which were published this May in the New England Journal of Medicine, the cockroach has been identified as a leading cause of severe asthma in inner city children. Specifically named as the culprit are the allergens cockroaches leave behind: allergens that are found in their feces, carcasses, shed skins, and egg cases. (The article, “The Role of Cockroach Allergy and Exposure to Cockroach Allergen in Causing Morbidity Among Inner City Children With Asthma,” by Dr. David Rosenstreich, et al., appeared in the May 8 issue.)

The federally funded, multi-million dollar National Cooperative Inner City Asthma Study, took place from 1991 through 1997. It was conducted by close to 100 researchers at eight universities in seven major urban centers across the U.S.: Washington, Cleveland, Chicago, St. Louis, Detroit, Baltimore, and two sites in New York. At least eight different pest control companies, and one industry supplier, Whitmire Micro-Gen, were involved. Thus, the broad base of information gained from participants across the study may have a profound impact on the pest control industry which will likely be felt on a national scale.

GOOD NEWS? For this industry, the cockroach finding appears to be good news. After all, pest control operators, working to keep the image of the industry in a positive light, have the much needed reliable third-party source working, for a change, on their side. And for consumers, especially those living in inner city areas and dealing with childhood asthma problems, this finding means perhaps there are ways the severity of the illness can be reduced. The finding even bodes well for hospitals, health departments and municipal governments, which have had to foot the bill for frequent emergency room visits, due to children’s severe bouts with asthma, and may now be able to help promote prevention.

Jay Nixon, one of the pest control operators who participated in the NCICAS study, pointed out that the role of cockroaches in childhood asthma was somewhat of a surprise to many involved in the study.

“This program was not necessarily about cockroaches when it started. It was a study to see why in the world is there such an increase in asthma in inner city kids,” said Nixon. “I don’t think many of these people would have predicted that cockroaches would have come out as significant as they have.” Other suspected irritants examined in the study included dust mites, mildew and second-hand cigarette smoke.

Nixon, who is president of American Pest Management, Takoma Park, Md., became a participant in the study at the request of Dr. Floyd Malveaux, dean of the college of Medicine at Howard University, Washington, D.C. His role has been to help the researchers understand cockroaches and their control, particularly in inner city households.

Nixon saw the study as a potential impetus for bringing a new sector of business to the PCO. “I was immediately interested that the medical community was interested in the topic of cockroaches,” he said.

Jay Nixon of American Pest Management.

Jay Nixon of American Pest Management.

UNANSWERED QUESTIONS. Despite the extensive nature of the study, a number of unanswered questions remain, particularly for PCOs eager to take advantage of the findings to market their services more aggressively. Considering the implications of this finding, and what remains to be seen, many say it’s still too early to make conclusions that can be applied to pest control.

One of the first and most obvious questions that arises from this research pertains to sanitation: If the cockroaches and their allergens are removed from a particular situation, will the asthma problems associated with that infestation also be reduced?

Dr. Peyton Eggleston, a pediatric allergist with Johns Hopkins University Medical Center, and a co-author of the journal article, is now hard at work on identifying the relevant questions, and setting out to answer them. “The first question is whether or not allergen removal would improve asthma. Before we can answer that, we have to have an effective method of cockroach allergen removal in an inner city population,” said Eggleston. He acknowledged the researchers were surprised to find that the combination of sensitivity and exposure to cockroaches was related to the severity of the asthma. “Once you’ve identified something like this, the assumption is that if you remove the allergen that you’ll improve the disease,” said Eggleston. “That has to be proven in a research study.” And that type of study, Eggleston said, both reducing the numbers of cockroaches and cleaning away the allergens left behind to reduce exposure to cockroaches, was examined in a phase of the original study. Eggleston is conducting a second, more extensive trial of removing remaining allergens in a new project sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.

Nixon points out that during the “intervention phases” of the NCICAS study, the researchers tried to identify whether cleaning up the cockroach allergens would offer relief to asthmatics. But finding an answer to that question has proved to be somewhat complex, considering the type of “cleaning” that is done. Which leads to another question: How clean is clean enough?

“Some places are so infested,” Nixon explained, “that if you removed every cockroach by tomorrow, there’s literally pounds of fecal material in there from the previous infestation.” And much of the fecal material, as well as shed skins and cockroach bodies is often located in such hard-to-reach places as behind walls or inaccessable voids.

According to Eggleston, the intervention phase of the study did show cockroach elimination to be beneficial, but involved many different types of treatment. Children improved, but it was not possible to identify allergen reduction as the cause.

Cockroach allergen levels, on the average, did not change in the study. Therefore, the new studies, including one spearheaded by Dr. Eggleston, will examine if, by hiring professional cleaners for the homes, the amount of cockroach allergens will be reduced enough to also lessen the severity of childhood asthma. In other words, the research may compare the effects of “a good spring cleaning,” as Nixon puts it, with a more thorough, aggressive type of sanitation. The research may also attempt to identify an “allergenic load,” or a threshold for the maximum acceptable amount of allergens, below which fewer asthma-related emergencies tend to occur. Eggleston also plans to conduct additional epidemiological studies to see if similar conclusions can be reached with other types of allergens.

“We understand there are many allergens, including pollen, dust, and molds. The fact that we’ve proven there’s an association in cockroaches is important in itself, but it also generates a need to look at allergens other than cockroaches,” Eggleston said. Therefore, future research will also focus on whether the severe cases of asthma are related to cockroach allergens specifically, or are connected with other allergens as well.

Regardless of the results of these studies, PCOs can use the information revealed by the NCICAS study to promote their own services for eliminating cockroaches, now that a direct link has been found between the pests and asthma.

FUTURE POSSIBILITIES. Pest control operators, stay tuned: Ongoing investigations of the topic of cockroach and other allergens means there is potentially more ground-breaking news ahead which could affect the pest control industry and its perceived value among consumers.

Depending on the results of the current studies, Nixon says, pest control operators of the future, especially those working in urban areas, may be able to earn some increased business, in an existing line of work with a new twist: professional pest control for cockroaches along with allergen removal. Furthermore, Nixon added, if allergen removal does become a realistic method proven to reduce the severity of asthma, local municipalities and health departments may find the cost to be highly preferable to repeated emergency room visits and hospital bills due to asthma-related illnesses.

Either way, Nixon says, there will definitely be an educational component associated with the findings behind this and related studies. “A lot of people now are going to have to recognize that cockroaches are more than just a bug with six legs.”

The author is associate editor of PCT.

TO RECEIVE A COPY OF THE ALLERGEN STUDY

The New England Journal of Medicine is a weekly journal which reports the results of important medical research worldwide. It is published by the Massachusetts Medical Society and is based in Boston, Mass.

To receive a copy of the study regarding cockroach allergens and childhood asthma, check with your local library or nearby university library to see if they subscribe to the New England Journal of Medicine. The report can also be ordered directly from the Journal for a fee, by calling the Customer Services Department at 617/893-0413 or 800/THE-NEJM. The report, “The Role of Cockroach Allergy and Exposure to Cockroach Allergen in Causing Morbidity Among Inner-City Children With Asthma,” by Rosenstreich DL, et al., appeared in the May 8, 1997, issue. And don’t forget about the World Wide Web. An abstracted version of the report may also be available on the Journal’s Web site: http://www.nejm.org/JHome.htm.

WANT MORE?

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the June 1997 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Pest Control Technology

- Target Specialty Products, MGK Partner for Mosquito Webinar

- Cockroach Control and Asthma

- FORSHAW Announces Julie Fogg as Core Account Manager in Georgia, Tennessee

- Envu Introduces Two New Innovations to its Pest Management Portfolio

- Gov. Brian Kemp Proclaimed April as Pest Control Month

- Los Angeles Ranks No. 1 on Terminix's Annual List of Top Mosquito Cities

- Kwik Kill Pest Control's Neerland on PWIPM Involvement, Second-Generation PCO

- NPMA Announces Unlimited Job Postings for Members