Who better to weigh in on the topic of insect biodiversity than renowned photographer and world traveler Tom Myers, a Board Certified Entomologist who has traveled the globe photographing insects from the Amazon rainforest to the grasslands of Africa and the Australian outback to the snow-covered wilderness of Antarctica?

Longtime colleague Jim Sargent said Myers’ “unbridled curiosity” about insects is what makes his work so special. “He shoots a photo and then he studies it and thinks about what he sees,” Sargent says. “He’s always acquiring knowledge.”

That knowledge gives Myers a unique “lens” into how insect populations around the globe are being impacted by both man-made and natural phenomena. “A lot of the stress insects are under is a result of habitat destruction,” he says. “I’ve gone to areas (in the Amazon) where we have done research one year and gone back two years later and the whole place has been burned. You have nothing but stumps.” In such situations, insect populations pay the price, both in biodiversity and biomass.

In the United States, urbanization and suburban sprawl create “urban deserts” where insect-rich fields once existed. This is where an understanding of insect biomass versus biodiversity is important. “In your backyard, for instance, you may have a large population of Japanese beetles, so in terms of insect biomass it looks great,” Myers says. “But for a healthy ecosystem, you also need insect biodiversity,” a variety of insect species populating a plot of land.

And how do you do that? Myers says it’s not that difficult. It may be as simple as allowing native plants to grow on highway medians; planting hedgerows to break up large expanses of farmland; or creating green space and parkland in urban areas. Local governments also can help by developing programs to promote the planting of a diversity of native plants on private and public lands, actions that would benefit local insects and birds.

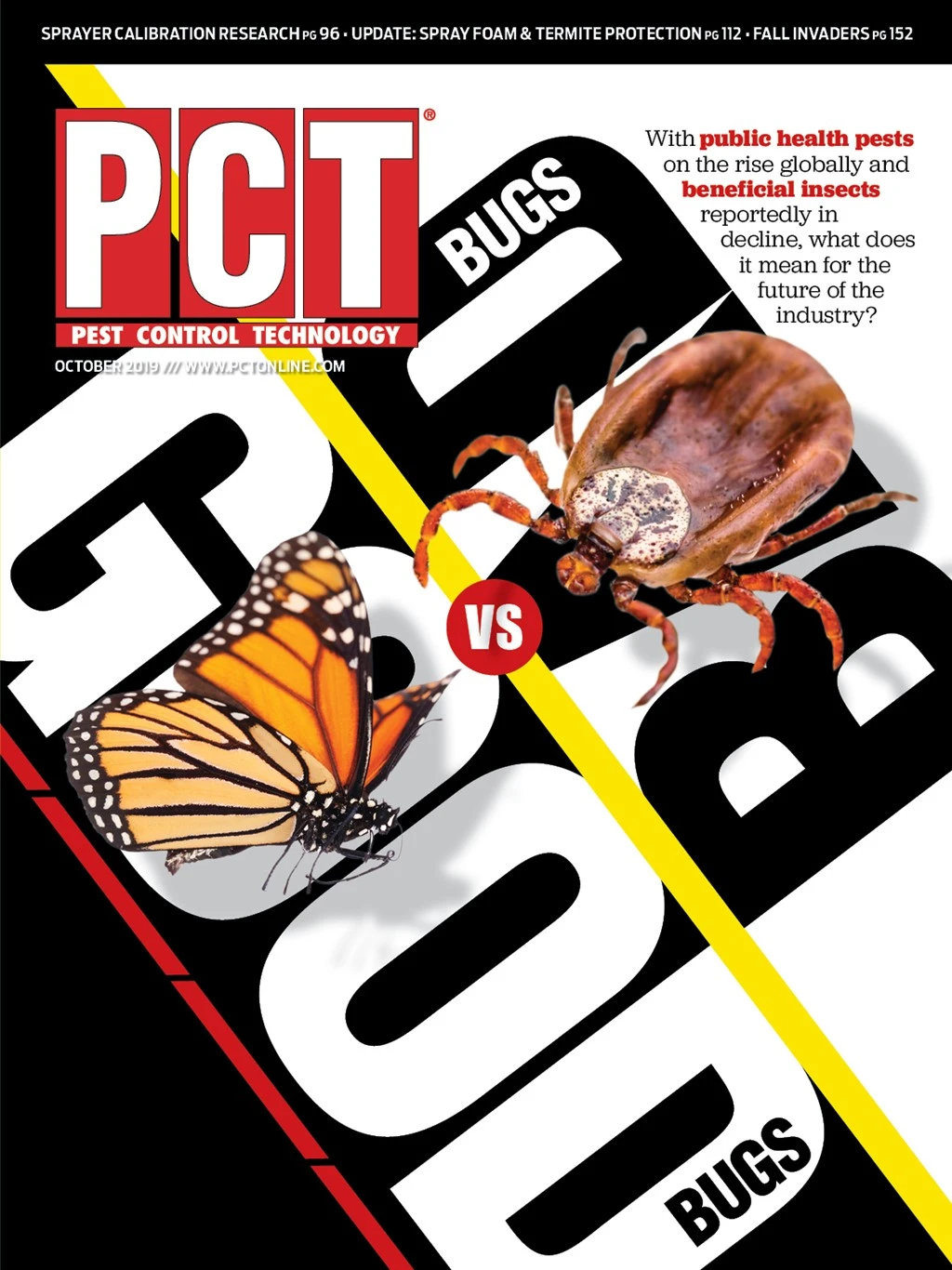

While public health pests remain a concern, Myers says it’s a misconception that problems are more prevalent today than at any time in the past. “If you look back 75 years, fly and bed bug problems were probably worse than they are now, but at the time they were accepted as the norm. Now, we don’t tolerate pest levels as we once did,” he says, while readily admitting that newly introduced invasive species represent an ongoing threat — and opportunity — for PMPs.

As someone who has devoted his career to insects, Myers says it’s important to keep the lines of communication open. “I think involving citizens in the discussion will help them understand the issue,” he says. “We’re all in this together.”

Explore the October 2019 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Pest Control Technology

- Donny Oswalt Shares What Makes Termites a 'Tricky' Pest

- Study Finds Fecal Tests Can Reveal Active Termite Infestations

- Peachtree Pest Control Partners with Local Nonprofits to Fight Food Insecurity

- Allergy Technologies, PHA Expand ATAHC Complete Program to Protect 8,500 Homes

- Housecall Pro Hosts '25 Winter Summit Featuring Mike Rowe

- Advanced Education

- Spotted Lanternflies, BMSBs Most Problematic Invasive Pests, Poll Finds

- Ecolab Acquires Guardian Pest Solutions