Photo: Pest and Diseases Image Library, Bugwood.org Photo: Pest and Diseases Image Library, Bugwood.org |

Although bed bugs have received the bulk of publicity in recent years, the various species of pest ants still hold the title as the number one invader of homes and businesses. Carpenter, Argentine, fire and pavement ants are still the most widespread and important ant pests, but in certain localities, various species are the prevalent pest, including a number of introduced, invasive species.

Invasive ant species are also known as “tramp” ants which have a shared list of traits that make them ideally suited to survival in a new environment without any of their usual natural enemies. Tramp species are highly adapted to living with humans, and, in fact, often are only seen in significant populations where humans have disrupted the natural landscape by development. These species are generally carried by humans in soil and belongings to new sites and new countries. For example, in the United States, the pharaoh ant is only capable of moving to new structures with the help of people.

Multiple-queen colonies are a benefit to successful pest ant species in that they enable a colony to survive even catastrophic die-offs of workers, if at least one queen and a few workers survive. Multiple queens also assist in successful establishment of numerous satellite colonies that can survive on their own if separated from the rest of the colony. Such factors provide significant advantages in survival.

Unicolonial behavior is a common but not universal trait among the tramp species. Argentine ants, for example, take advantage of independent colonies merging together to increase the ability to exploit resources and ensure survival. Odorous house ants, however, are not generally unicolonial, and workers from separate colonies are typically antagonistic to one another. During the peak summer period of activity, Argentine ant colonies will merge with each other to form huge extended supercolonies that may stretch across several properties. This factor is also seen among the white-footed ant and some species of big-headed ants, particularly P. megacephala.

Interspecific aggression involves the competitiveness of a tramp species against other ant species in its territory. The Argentine ant is a fierce competitor, often driving other ant species completely out of its foraging range. In some areas where this species has been present for many years, native ant species are almost nonexistent.

Colony dispersal by budding and fission is of benefit to species dependent upon man for dispersal. Species that propagate by budding can form new colonies at any time instead of being restricted to mating flights timed at certain annual periods. This ensures that more new colonies can be produced in this manner, although the dispersal distance is greatly limited (pending involvement of people).

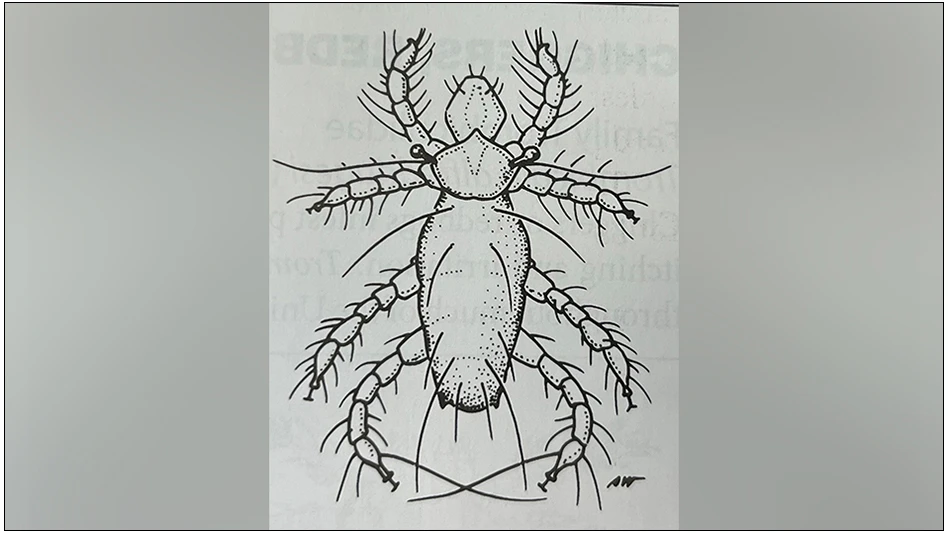

Most tramp species are monomorphic, having only one size of worker. The workers are typically small in size, rarely reaching above 3/16 inch (6 mm). Monomorphic workers are rarely specialized and can assume any task within the colony. This is especially important because satellite colonies can often be quite small, and new colonies started by budding require versatile workers. An exception to this rule is the African bigheaded ant, Pheidole megacephala, a pest in Florida and Hawaii, which is dimorphic, having two worker sizes.

Tramp “Queens.” By far, the most accomplished invasive species is the Argentine ant, Linepithema humile, which has become established in countries throughout the world. It arrived in the U.S. around 1900 and is the predominant pest ant in California. It is also important in parts of states along the Gulf Coast, from Texas to Florida, and in Hawaii.

Argentine ant, Linepithema humile. Photo: Natasha Wright, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Bugwood.org. Argentine ant, Linepithema humile. Photo: Natasha Wright, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Bugwood.org. |

Another important tramp species is the little fire ant, Wasmannia auropunctata, which is found in Florida and Hawaii and is a minor pest. This species, however, is a major pest in many countries, particularly in agriculture where they sting field workers. The long-legged ant, Anoplolepis gracilipes, is another minor tramp species in the U.S. (Hawaii) but is a major pest elsewhere in the world where it can decimate populations of ground-nesting birds in some South Pacific Islands.

Other important tramp species in the U.S. include the ghost ant, Tapinoma melanocephalum; the African bigheaded ant, Pheidole megacephala; the pharaoh ant, Monomorium pharaonis; common crazy ant, Paratrechina longicornis; robust crazy ant, Nylanderia bourbonica; and the difficult ant (misidentified as the white-footed ant), Technomyrmex difficilis.

Native “Invasive” Species. In the past 15 years, one ant species native to this country has developed tramp-like characteristics and suddenly became an invasive ant species in areas where it had always been present but wasn’t seen much inside buildings. The odorous house ant, Tapinoma sessile, generally developed small- to medium-sized colonies which were antagonistic to one another. In areas such as the Mid-south and Northern California up through Washington, the odorous house ant (OHA) was a structural pest but not necessarily one that was considered exceedingly difficult to control.

Odorous house ant, Tapinoma sessile. Photo: Joseph Berger, Bugwood.org Odorous house ant, Tapinoma sessile. Photo: Joseph Berger, Bugwood.org |

In the 1990s, the OHA began to be seen inside homes more often in Kentucky, Indiana and along the Atlantic Coast. The difference today is that the infestations are now more difficult to control. Entomologists remain uncertain as to the reasons for the change in the OHA behavior, but it seems clear that this species is now forming huge colonies similar to those seen with Argentine ants.

I have a theory — unproven — that the OHA uprising coincides with an increase in residential landscaping. I have found this species inside bags of mulch products stored at homes. Whether the ants were inside the mulch bags when they were purchased, or simply moved in after the fact, is not known. What is clear is that the OHA and many of these tramp species love damp landscape mulch and leaf litter in which to nest.

About 12 to 14 years ago in Memphis, I accompanied a Terminix Service professional on his daily route. At one house, we uncovered approximately a dozen OHA nests in landscape mulch along a home foundation. The customer told us he had put the mulch down and planted all the new plants just a few days prior. Before that, the ground had been barren with patches of grass. The ants had moved into the beds from the surrounding yard taking advantage of the new moist harborages afforded by the mulch.

Another formerly non-pest species that has become a significant problem in central Florida is the black pyramid ant, Dorymyrmex medeis. This species has been present in central Florida for years but recently has begun forming huge colonies in some yards. Individuals who have observed these populations have described the lawn as “moving with ants.” One colleague had his camera damaged by these pyramid ants swarming onto and into it when he placed the camera on the ground while filming the ants.

Pyramid ants are identified by the pyramid-like bump present on the top rear of the thorax when viewed from the side. The colony is formed in the soil with a small crater of soil piled around the opening.

New Kids on the Block. During the past 20 years, a number of exotic ant species have become established within the U.S. and are expanding their territories. One in particular, the hairy crazy ant, Nylanderia pubens, may well be the most difficult of any ant to control. The other species listed here are more localized and problematic, being easier to control when found. They include:

European Fire Ant, Myrmica rubra — This species is currently confined in the New England area, in particular Massachusetts and the surrounding states, including New York. Although not a true fire ant, this species does inflict a painful sting. It prefers nesting in landscape beds in mulch and leaf litter, but can also be found in lawns. In heavily infested areas, many nests can be found close to one another. These red and brown ants can be recognized by the sculpturing or grooves on the head and thorax (similar to that on pavement ants) and the fairly long spines on the top rear of the thorax.

Asian Needle Ant, Pachycondyla chinensis — Workers of this ant are about five millimeters long, dark brown to black with the legs and mandibles a lighter, orangish-brown color. The node is large and block like. Asian needle ants can inflict a painful sting and are found from parts of Virginia down through the Carolinas and west through Georgia into Alabama and locales in eastern Tennessee.

Related “pavement” ant, Tetramorium tsushimae. Photo: Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org. Related “pavement” ant, Tetramorium tsushimae. Photo: Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org. |

This species forms small colonies and nests in the soil under items such as landscape timbers, rocks and pavers, as well as mulch and leaf litter. Workers do not attack en masse like fire ants but do sting when trapped against the skin.

Related “Pavement” Ant, Tetramorium tsushimae — This ant has no formal common name but it is closely related to the pavement ant. In fact, in and around St Louis, Mo., this species has been observed displacing its pavement ant cousin from areas where it has been firmly established for decades. T. tsushimae is difficult to distinguish from the pavement ant requiring an experienced ant taxonomist to identify it.

Dark Rover Ant, Brachymyrmex patagonicus — This tiny (1.6 mm) dark brown ant is recognized by its nine-segmented antenna. Originally from Argentina, the dark rover ant is found along the Gulf Coast from northern Florida over to central Texas and has been found in South Carolina, Arizona and Nevada. Nests are located in soil and rotting wood. Around homes, dozens of small colonies can be found with ants from multiple colonies foraging onto and into the home.

The large number of colonies is what makes this species difficult to control. Bait or treat one or two colonies out of existence and others move in to occupy their territories.

Hairy Crazy Ant, Nylanderia pubens — The hairy crazy ant is also known as the Caribbean crazy ant and is by far one of the most difficult pest ants to control. It is found in Southeast Florida up to Central Florida as far north as Gainesville. It is primarily spread through shipments of landscape plants, shipping containers and similar goods. A related species, Nylanderia near pubens, is found in many counties in Southeast and Central Texas.

Hairy crazy ants develop extremely large colonies, possibly numbering more than a million workers living in multiple nests connected by trails. The worst infestations tend to be in buildings that back up to fields or wooded areas. Although the buildings are treated and thousands of ants are killed, live ants continue to pour out of these neighboring properties often overwhelming treatment efforts.

Around buildings, subcolonies of hairycrazy ants can be found in the same locations as other tramp species: in leaf litter, mulch and piles of items; under landscape timbers and stones; etc. I have found trails of these ants tunneling under sod and the thatch layer from the perimeter of the property to a home, thus evading treatment efforts directed at the lawn.

Hairy crazy ants forage onto buildings in such great numbers, they wear insecticide treatments off surfaces, sacrificing thousands but blazing a trail for following hoards to safely move through.

Managing Invasive Species. Species such as the European fire ant, Asian needle ant and T. tsushimae have smaller, more localized populations and can usually be controlled by locating and directly treating colonies. Dark rover ants, black pyramid ants and hairy crazy ants take more concerted and comprehensive efforts where large infestations occur.

A number of baits have been developed that will attract dark rover ants and on which they will extensively feed. Because a colony is typically small, if the bait is taken, control of that colony is fairly assured. The problem with a heavy infestation is that literally dozens of colonies could be involved, and for baits to work, each foraging trail needs to be baited and each foraging trail must accept and feed upon the bait. Dark rover ant management involves use of baits together with finding and treatming colonies and applying perimeter treatments to sites on buildings where ants are foraging or might enter.

Black pyramid ants also call for an integrated approach where baits and targeted treatments are used. Liquid ant bait feeders may be placed at the base of trees and shrubs in which workers may be foraging and also along the property perimeter. Care should be taken to keep children and pets away from liquid ant bait feeders. Granular baits placed along trails may also be helpful. Treatment of the building foundation and entry points can help limit ants that try to enter. Application of a granules insecticide like Talstar Xtra can be helpful in some situations. Follow label directions.

Where hairy crazy ants are plaguing a home or building, weekly or bi-weekly service may be needed to help keep the ants at bay. Liquid ant bait feeders can be important to give the ants a set resource site on which to forage away from the building. With large populations, the feeders may need to be replenished weekly during the warm summer months. Perimeter treatments to foundations have limited, often short-term effectiveness. Use of insecticide granules such as Talstar Xtra or TopChoice may provide relief in some cases. The key is persistence, with frequent service visits necessary in some cases.

The author is director, Technical Services, Terminix International, Memphis, Tenn. To contact Hedges, write shedges@giemedia.com.

Explore the April 2012 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Pest Control Technology

- FORSHAW Announces Julie Fogg as Core Account Manager in Georgia, Tennessee

- Envu Introduces Two New Innovations to its Pest Management Portfolio

- Gov. Brian Kemp Proclaimed April as Pest Control Month

- Los Angeles Ranks No. 1 on Terminix's Annual List of Top Mosquito Cities

- Kwik Kill Pest Control's Neerland on PWIPM Involvement, Second-Generation PCO

- NPMA Announces Unlimited Job Postings for Members

- Webinar: Employee Incentives — Going Beyond the Annual Raise

- Pest Control Companies Helping Neighbors in Need Eradicate Bed Bugs