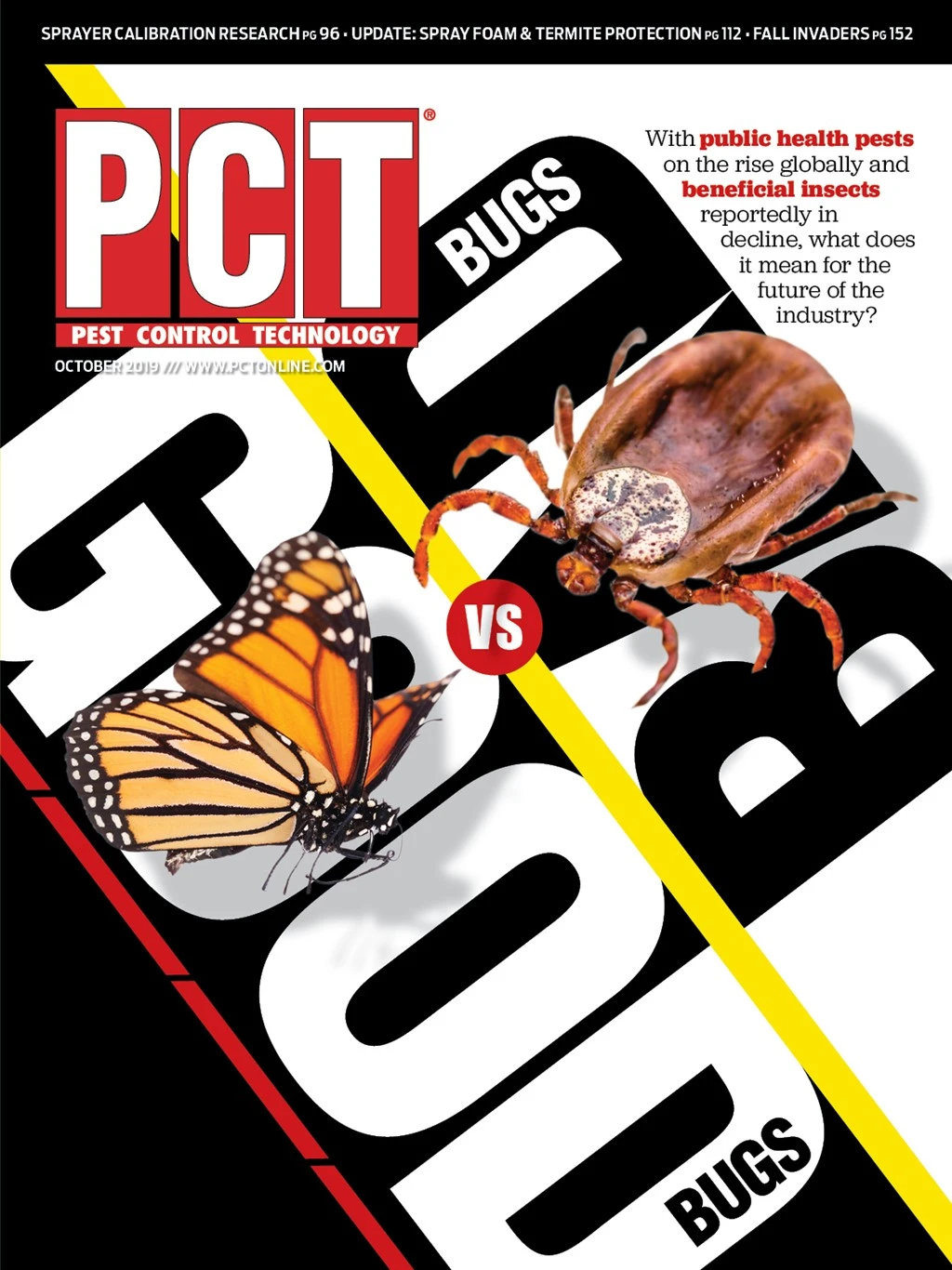

Despite seeming ironic on the surface, pest management professionals know that many insects are beneficial. Why? Because certain insects are valuable and helpful to our environment and ecosystem, and that message needs to be communicated to today’s well-informed and engaged consumers.

There are nearly 1 million known insect species in the world but only one to three percent are ever considered a threat to humans, structures or crops. That leaves a lot of insects doing what insects do, and many of those activities benefit people and the environment.

Today, there is a concern that many of the insects that benefit us are in jeopardy. In a report published earlier this year in the journal Biological Conservation, researchers revealed dramatic rates of decline that could lead to the extinction of 40 percent of the world’s insect species over the next few decades.

It’s important, however, to differentiate between beneficial insects and pests. While there are reports of beneficial insects on the decline, the National Pest Management Association told PCT that such studies “focused primarily on larger rural insect populations and tropical arthropods....We’re not seeing any decreases in urban pests such as cockroaches, ticks and ants...” (See NPMA’s full statement in the Editor’s column.)

In regards to beneficial insect decline, while the honeybee, monarch butterfly and various species of beetles are some of the most recognizable insects threatened, there are hundreds of species at risk.

The driving factors behind this include habitat loss and conversion to intensive agriculture and urbanization, the use of pesticides, biological factors (including pathogens and introduced species) and climate change.

BENEFICIAL INSECTS. Insects make positive contributions by:

- Preying on Pest Insects — Certain pests, like spiders, are predators of insects. So are some types of beetles, flies, true bugs and lacewings.

- Parasitizing Pest Insects — Parasitic insects, like some small wasps, lay their eggs inside insects or their eggs and this can help drive pest populations down.

- Pollinating Plants — Insects like native bees, honeybees, butterflies and moths can provide this service, helping plants bear fruit and other crops.

- Beneficial Animals — Birds and bats are examples of animals that can feed on pest insects.

Beneficial insects act as biological vacuum cleaners and help promote the cycle of life and natural balance of the ecosystem. Springtails and earthworms are soil recyclers, and without them the soil in your yard or neighborhood park would be hard as a rock. Termites are also soil recyclers but they have a less appealing side to them as well.

When ants are seen crawling across the kitchen floor, they are a pest that needs to be eliminated. On the flipside, when ants forage outdoors they are beneficial since they eat damaging turf pests, including white grubs and webworms. The same can be said of spiders and parasitic wasps.

In recent years the pollinator issue has been at the forefront of the beneficial insect debate and the pest management industry has been proactive in its response and recognition of the importance of pollinators.

Just how important is pollination? Dr. Mike Potter, extension professor at the University of Kentucky, says research has shown that one of every three bites of food we eat was made possible by bee pollination. And it’s just not the honeybee. There are more than 5,000 species of wild bees in North America and many are more abundant and efficient pollinators than the honeybee. They not only pollinate the crops we eat but ones that livestock (e.g., alfalfa) and wildlife rely on as well.

“Honeybees are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to pollination,” says Potter. “Wild bees in urban areas are very prolific and contribute greatly to the pollination of wildflowers, trees and shrubs that deliver environmental benefits (cooling the earth, carbon sequestration, etc.) but also serve as food and habitat for other wildlife.”

The loss of beneficial insects not only deals a blow to the ecosystem but leads to lost opportunities in science.

Dr. Mike Merchant, professor and extension urban entomologist with Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service in Dallas, says that the loss of insect life due to human activities could create a domino effect on plants, animals and the ecosystem that holds them together.

“While losing an insect species might not seem to be a big deal to many people, the true loss is not always immediately apparent,” says Merchant. “When an insect becomes rare, or goes extinct, it affects other species in nature.”

RECONCILIATION ECOLOGY. Today’s consumers have greater access to information — although not always accurate — and are paying more attention to the growing loss of beneficial insects in our ecosystem. While it doesn’t rise to the same volume as the conversation on climate change, the issue has found its niche in the ecological world and has been christened “reconciliation ecology.”

Reconciliation ecology studies ways to encourage biodiversity in human-dominated ecosystems. Unlike traditional conversation which sets aside large tracks of land (i.e., national parks) for preservation, reconciliation ecology focuses on investing in and maintaining species diversity in urban areas where people live and play.

How popular is this concept of reconciliation ecology with consumers?

Look at the volumes of information featured on social media, websites and pages of parenting and home improvement media outlets that talk about the value of creating a backyard that promotes plant and animal wellness. And big box home improvement giants Lowe’s and Home Depot now tag flowers and plants that support strong backyard ecosystems.

“We live in an ecosystem that functions a little like a jet airplane,” says Merchant. “Remove a single rivet from an airplane and it can hold together by shifting stress to other parts of the plane. But keep removing bolts and eventually you risk catastrophic failure. You never know what the key rivet is until it’s gone. This is why biologists get nervous about reports of declining insect populations. There is no way that such changes are good for the ecosystem — or for people in the long run.”

Merchant says that in the eyes of many, pesticides are one of the big contributors to this decline of nature. Articles about declines in honeybee numbers, for example, usually mention pesticides as part of the problem. This can affect how the public perceives us in the pest control industry.

“The good services pesticides provide can get overlooked in the debate,” said Merchant. “We in the pest control industry know that when pesticides are used responsibly they can protect public health and property. I think consumers need to hear that our industry cares about nature too. Only then will we be seen as something more than ‘bug killers.’”

Savvy PMPs know that consumers will align themselves with brands they feel are aligned with their beliefs. It will take not only targeted messaging in consumer-facing advertising and marketing but designing pest programs that go the extra mile to protect beneficial insects.

“Pest managers must demonstrate they are sensitive to the issue and are conservation minded when it comes maintaining a diverse ecosystem that includes beneficial insects,” says Potter. “There is a huge opportunity for our industry to tell the story and get in front of this issue.”

In a recent Associated Press story on the decline of beneficial insects, University of Delaware entomologist Doug Tallamy said there would be a total ecosystem collapse if insects were lost. He added, “If they (insects) disappeared, the world would start to rot.”

Kentucky’s Potter shares his fellow scientist’s concerns and says conditions are getting worse. “It is a complicated, contentious issue, but we must acknowledge the fact that climate change does impact insects.”

The author is a communications and marketing consultant with B Communications.

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the October 2019 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Pest Control Technology

- Hygiene IQ Uses Smart Sensor Technology to Detect Rodents

- Rollins Acquires Saela Pest Control

- PCT Spotlights Leaders in Pest Management for Women’s History Month

- Honey Bee Colony Losses Could Reach up to 70 Percent, WSU Researchers Report

- SiteOne Hires Dan Carrothers as Vice President of Agronomic Business Development

- U.S. Structural Pest Control Market Grew Nearly 8% in 2024, Specialty Consultants Reports

- Hands United Foundation Supports PMPs in Hardship Through Financial Relief

- Proven Pest Exclusion Solutions