Although there are about 2,500 species of fleas worldwide, only about 325 appear in the United States. The cat flea is the predominant species PMPs encounter in homes. In fact, more than 90 percent of the fleas found on pets, as well as feral dogs and cats, are cat fleas, according to the Mallis Handbook of Pest Control. A look into the biology of the cat flea reveals why these parasites are so difficult to control and why insect growth regulators (IGRs) are effective in treating them.

The Life Cycle

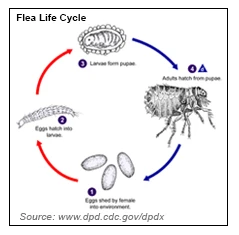

Within a day of attaching to a host and taking her first blood meal, a female flea mates and, two days later, begins laying eggs at a rate of about one per hour for the rest of her three- to five-week life. These eggs are smooth and don’t stay in the host’s fur very long. Every time the host dog or cat moves, eggs drop into the environment. If the pet is social, that’s likely the living room, family room or another high-traffic area.

The eggs hatch in two to five days, depending on temperature and humidity, and the emerging larvae often burrow into carpet, upholstery or bedding, where they mature and move into the next stage of development, pupation.

During pupation, the aspiring adult spins a silk cocoon, where it matures within a week or two. It can then continue to live inside the cocoon for weeks or months waiting for a host. When heat, vibration, carbon dioxide or pressure indicates a potential host is near, the flea emerges and flings itself toward the host. If successful, it attaches and begins to feed on the animal’s blood. If it is unsuccessful, it must find a host within several days or die.

Why IGRs?

Adult fleas are very difficult to kill; they can be much more challenging to treat than other pests, says Dr. Nancy Hinkle, professor of veterinary entomology at the University of Georgia. In part, that’s because when fleas emerge from their cocoons to attach to a host, they might never touch the treated floor, or they hop across it too quickly to pick up a lethal dose of the insecticide.

Hinkle explains: “Unlike cockroaches, which are very good about picking up and ingesting insecticides because they are low to the ground and continually groom themselves, fleas have a mouthpart that’s only good for sucking blood, so they don’t groom. That means they don’t ingest the insecticides that are applied. If they stayed on the ground long enough for the chemical to penetrate their exoskeleton, they would die — but they don’t. This is why it’s so important for the host pet to be treated: because insecticide can be transmitted to the parasite through the host’s blood.”

It’s also why IGRs are so important: because they address the other stages of the flea’s life cycle, preventing eggs, larvae and pupae from becoming functional, reproductive adults.

“Larvae and eggs are very susceptible to IGRs,” says Hinkle. “IGRs can penetrate the egg and kill the embryo, or they can disrupt the molting process and prevent formation of the cuticle so that progression to the next stage becomes impossible.”

PMPs who use IGRs as part of their flea treatment protocol tend to achieve longer-term control, fewer callbacks and increased customer satisfaction. Andrew Taylor, technical director and entomologist at Clegg’s Termite & Pest Control, shares, “You could spray insecticide onto the flea pupae all day long, but you’ll never penetrate them. Unless you’re using something that acts on the flea’s metabolism — an IGR — you’ll end up coming back to that account again and again.”

Latest from Pest Control Technology

- Donny Oswalt Shares What Makes Termites a 'Tricky' Pest

- Study Finds Fecal Tests Can Reveal Active Termite Infestations

- Peachtree Pest Control Partners with Local Nonprofits to Fight Food Insecurity

- Allergy Technologies, PHA Expand ATAHC Complete Program to Protect 8,500 Homes

- Housecall Pro Hosts '25 Winter Summit Featuring Mike Rowe

- Advanced Education

- Spotted Lanternflies, BMSBs Most Problematic Invasive Pests, Poll Finds

- Ecolab Acquires Guardian Pest Solutions