Shannon Sked

Editor's note: Shannon Sked, B.C.E., who co-authored the study, discusses what surprised him, what the challenges were and more in a video.

The public health impact of bed bugs in multifamily dwelling (MFD) communities is well established (Reinhardt and Siva-Jothy 2007, Doggett et al. 2012, Aultman 2013) and is both costly (Wang et al. 2009, Potter et al. 2013, Stedfast and Miller 2014) and difficult (Doggett et al. 2012) to control. Successful bed bug management in MFDs has been difficult for the industry to achieve since control strategies are typically reactive, lacking a proactive monitoring system to detect novel introductions or dispersing populations (Romero et al. 2017).

Current bed bug management strategies in MFDs often rely on resident complaints followed by reactive insecticidal treatments. There are several reasons why this process can lead to less-than-ideal results. First, resident complaints are unreliable in identifying infestations (Wang et al. 2016, Wang et al. 2019, Abbar et al. 2022). Additionally, MFD property managers of low-income communities are often limited to low-bid public contracts that offer a “pay-per-treatment” service, limiting the number of sequential treatments that would be affordable. Since multiple treatments are often required for successful elimination (Potter et al. 2008), the limited number of treatments can be insufficient. To complicate things further, improper preparation leads to treatment refusals (Potter et al. 2015), leaving infestations in place for long periods and subsequently leading to the spread of bed bug infestations throughout buildings (Cooper et al. 2015).

Mattress encasements have been demonstrated to be an effective tool in bed bug integrated pest management (IPM) programs (Wang et al. 2009, Doggett et al. 2011) and the adoption of encasements as an IPM tactic has been widely accepted (Wang et al. 2017). Encasing mattresses can provide immediate population reduction as the majority of bed bugs in most infestations are associated with the mattress, especially the box spring (Pinto et al. 2021).

Additional benefits of encasements include reducing available harborage locations and simplify detection during inspections (Cooper 2007) and trapping bed bugs that were already present on or inside mattresses and box springs until they starve when they are installed properly (Wang and Cooper 2011), making it unnecessary to discard infested beds.

Bed bug management in MFDs often includes the use of mattress encasements (National Center for Healthy Housing 2010, Goldberg 2015, Singh et al. 2017). However, the cost of a fabric encasements is considerably higher than that of vinyl encasements. Data from five years ago show that the price for fabric encasements was $25 to $90 per encasement, compared to $6 to $10 per vinyl encasement (Singh et al. 2017). While vinyl encasements are much more affordable, they are less durable and often tear easily.

The research team at Rutgers University Urban IPM laboratory has conducted field research on bed bugs for years. One observation that has been consistent during these field studies is that bed bugs are: 1) less likely to be found in mattresses and box springs with encasement than those without encasement, and 2) less likely to be found on vinyl encasements than fabric encasements. This has been observed repeatedly over the years. These observations show that the presence of encasements on mattresses and box springs, as well as the material used to manufacture the encasements present, has an impact on bed bug distribution.

It is suspected that a decrease in the number of refugia opportunities through the use of encasements should assist in identifying infested apartments and reducing bed bugs in infested apartments. However, this has never been formally studied. Without a better understanding of how bed bug distribution changes in the presence of encasements, it is not clear if the presence of encasements supports management efforts, impedes those same efforts or has no significant impact. We therefore designed a study to evaluate the impact of the presence of encasements and the encasement material type (vinyl or fabric) on bed bug distribution.

The Study: Simulating a Bed Complex

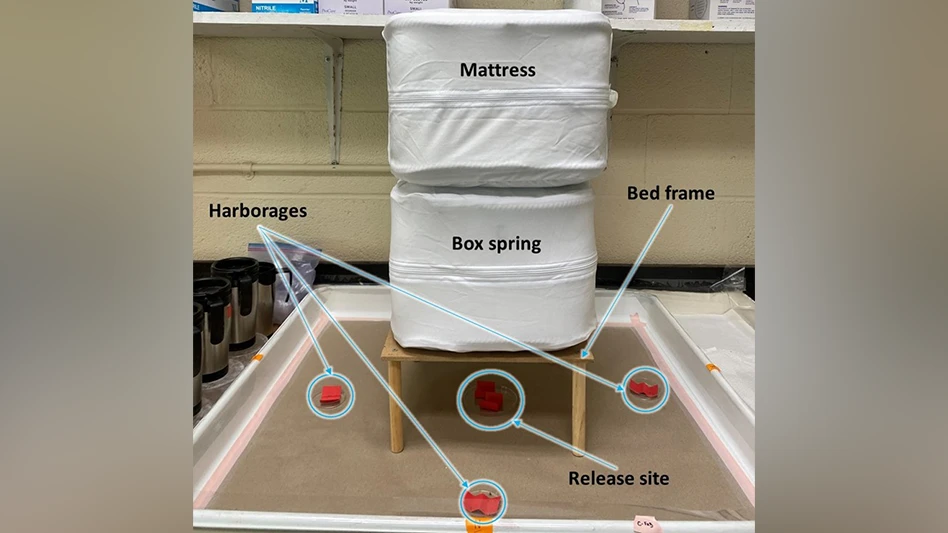

Three arenas with miniature bed complexes on plastic trays (80 centimeters by 75 centimeters by 5 centimeters) were set up (Figure 1, above) in a walk-in environmental chamber (around 21 degrees Celsius, around 30-40 percent relative humidity and 12:12 (light:dark photoperiod). Miniature replicas of mattresses and box springs (33 centimeters by 33 centimeters by 23 centimeters) were placed on similar-sized fabricated bed frames in the middle of each arena to mimic a bed complex.

The mattresses and box springs were encased in either a vinyl or fabric encasement (Cleanbrands LLC, Warwick, R.I.), manufactured to size for this study or left without an encasement. The vertical inner walls of each arena were coated with a light layer of fluoropolymer resin, and around 7 centimeters wide clear packing tape was adhered to the inside edges of the arena trays to prevent escape. A piece of folded red card paper, previously used to rear bed bugs, and 10 bed bugs exuvia were placed inside a petri dish (6 centimeters diameter, 1.5 centimeters height) and placed along each side of the arena to mimic harborage sites.

One hundred bed bugs (Irvington strain, collected from apartments in 2012) were starved for seven days and then released at the beginning of the dark cycle in the center of each arena, underneath the bed frame. The ratio of third through fifth instar nymphs, female adults and male adults was 80:10:10, respectively, which mimics the natural population stage-distribution of bed bugs (Wang et al. 2010).

To serve as a bed bug host attractant, a 20-ounce coffee mug containing 315 grams of dry ice was placed on top of the mattress at the time that bed bugs were released (Wang et al. 2011, Singh et al. 2015). The lid of the coffee mug had a roughly 5-centimeter diameter opening to allow for CO2 to escape. The CO2 release rate was approximately 249 milliliters per minute, which is similar to that of an adult’s respiration rate.

Bed bugs were allowed to wander the arena freely throughout the dark cycle. Approximately 12 to 13 hours after the bed bugs were released, bed bugs were collected from the various locations within each arena including the mattress, box spring, bed frame, arena floor and harborages. The numbers collected from each location and the stage of the bed bugs (adult male, adult female or nymph) were recorded.

The experiment was repeated five times over a three-month period. New encasements, mattresses, box springs and bed frames were used in each replicate. The total number of bed bugs found in each location was summarized for each replicated experiment. Bed bugs that remained at the release site were not included in the summary analysis since they were not considered active, and this study was designed to investigate distribution patterns between mattresses and box springs with or without encasements, as well as between different types of encasement materials. The proportion of bed bugs found in each location was then statistically analyzed using linear models.

When analysis of variance showed significant differences between the three groups, pairwise comparisons were tested using Tukey’s HSD tests. Significant differences in where bed bugs were located within the arenas between the three encasement groups were evaluated using this statistical process.

Results: Significant Differences in Distribution Patterns Observed

The mean proportions of bed bugs collected from each location at the end of the experimental periods are shown in Figure 2 (below). Differences in the proportion of bed bugs found on the box springs, mattresses, bed frames and arena floor were observed between fabric, vinyl or no encasement replicates. A significantly lower proportion of bed bugs was found on the mattresses in the group that had vinyl encasements (2 percent) compared to those encased in fabric (16 percent) or without encasement (15 percent).

Additionally, a significantly lower proportion of bed bugs were found on the box springs in the group that had fabric (7 percent) or vinyl encasements (4 percent) compared to those with no encasements (36 percent). A significantly greater proportion of bed bugs were found on the bed frame in replicates with vinyl encasements (69 percent) and fabric encasements (63 percent) compared to no encasement (45 percent). The proportion of bed bugs found on the arena floor was also significantly different, with vinyl having the highest proportion collected (22 percent) compared to fabric (13 percent) and no encasements (3 percent). No significant differences were found in the proportion of bed bugs found in the harborages between the three encasement treatment groups.

The results above imply that installing either fabric or vinyl encasements may reduce the proportion of bed bugs on the box spring and that vinyl encasements may also reduce the proportion of bed bugs on mattresses and increase the proportion of bed bugs in other areas off of the bed complex. Additionally, encasements may increase the proportion of bed bugs on bed frames; at least when constructed similarly to the mini-bed frames used in this study (platform-style). Based upon our findings, future research is warranted comparing differences between platform and open style bed frames as well as the effect of including bed linens on the encased mattresses.

What Do These Findings Mean for the Field Practice?

This study considered the impacts of encasement presence and the type of material used to manufacture the encasements on bed bug distribution in a small spatial-scale controlled laboratory setting. By reducing harborage opportunities, a lower proportion of bed bugs were found on the box springs when encasements were present. The presence of encasements caused a higher proportion of bed bugs to aggregate on the bed frames and arena floors compared to when no encasements were present.

It is important to understand that the absence of linen sheets and the style of bed frame used in this study may have contributed to the higher proportion of bed bugs found on the bed frames. If fitted sheets were present, there is a likelihood that the bed bugs would have moved to the sheets as well. Based upon our numerous field observations, we expect movement of bed bugs into the fitted sheets and linens to be associated mostly with vinyl encasements and not fabric.

In our study, the design of the bed frame was such that the box spring rested on a flat board, similar to that of a platform bed, creating a plethora of harboring opportunities for wandering bed bugs at the box spring-bed frame junction, as well as between the box spring and platform. If the bed frame had been a metal open-frame style rather than a wooden platform, bed bugs may not have preferred the bed frame as much as what was observed in this study when encasements were present.

What is important is that the presence of encasements caused the bed bug distribution to change when compared to the distribution found with no encasements present. Previous studies have demonstrated the importance of inspecting for bed bug activity in areas away from sleeping and resting areas (Cooper et al. 2015). Our findings reinforce this point and suggest the presence of encasements may further facilitate movement of bed bugs from predictable locations such as the mattress and box spring. In areas where encasements are deployed in a bed bug IPM program, technicians would need to pay more attention to bed frames, linens and other items on the beds, as well as areas surrounding the bed complex.

Further, there were more bed bugs found away from the mattress and box spring for those that had vinyl encasement installed than what was found when fabric encasements were installed. Had we placed linens on top of the encased mattresses in this study, we presume that we would have found a higher proportion of bed bugs in the linens in the vinyl encased group based upon what has been observed during our field inspections (unpublished findings).

Still, these results demonstrate the importance of inspecting the bed frame, as well as other aspects of the bed complex, such as a headboard. It is logical to assume that bed bugs avoid encased mattresses and box springs but remain on other parts of the bed complex such as the headboard or bed frame when encasements are present. In all three treatment groups in this study, bed bugs were found mostly on the simple wooden platform or “table-top” style bed frame.

The Benefit of Using Encasement Include:

- Reduction of the populations associated with mattresses and box springs (especially inside complex box springs).

- Improved ease of visually inspecting for bed bugs still associated with mattresses and box springs during follow-up services.

- Ease of removing exposed bugs on the smooth surface of encasements during follow-up services.

- Reducing economic losses by having to otherwise dispose of mattresses and box springs.

The results of this study highlight the importance of also considering how distribution patterns can vary depending on the presence of encasements and the type of materials used to manufacture them. If inspections and treatments overlook these differences in distribution, bed bug infestations could be challenging to identify and eliminate.

Finally, the affordability of vinyl encasements would make them cost-effective for use in IPM programs in low-income multifamily dwellings. The cost differential justifies their use in environments where limited budgets must be considered in making bed bug management decisions.

Acknowledgement:

This research was funded by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development Healthy Homes Technical Studies grant program (grant number NJHHU0039-17), National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture Hatch project NJ08127, through the NJ Agricultural Experiment Station.

References:

Abbar, S., R. Cooper, S. Ranabhat, X. Pan, S. Sked, and C. Wang. 2022. Prevalence of cockroaches, bed bugs, and house mice in low-income housing and evaluation of baits for monitoring house mouse infestations. J. Econ. Entomol. 59: 940–948.

Aultman, J. E. 2013. Don’t let the bedbugs bite: the Cimicidae debacle and the denial of healthcare and social justice. Med. Health Care Philos. 16: 417–427.

Cooper, R. 2007. Just encase: mattress and box-spring encasements can serve as an essential tool in effective bed bug management. Pest Control 75: 64–75.

Cooper, R., C. Wang, and N. Singh. 2015. Mark-release-recapture reveals extensive movement of bed bugs (Cimex lectularius L.) within and between apartments. PLoS ONE 10: e0136462.

Doggett, S. A., C. J. Orton, D. G. Lilly, and R. C. Russell. 2011. Bed bugs: The Australia response. Insects 2: 96–111.

Doggett, S. L., D. E. Dwyer, P. F. Penas, and R. C. Russell. 2012. Beg bugs: Clinical relevance and control options. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 25: 164–192.

Goldberg, G. 2015. Understanding essential quality characteristics of mattress and box spring bed bug encasements. Int. Pest Control. 57: 156–157.

National Center for Healthy Housing. 2010. What’s working for bed bug control in multifamily housing: Reconciling best practices with research and the realities of implementation. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Pesticide Programs. pp. 9–15. https://nchh.org/resource-library/report_what's-working-for-bed-bug-control-in-multifamily-housing.pdf.

Pinto, L. J., R. Cooper, and S. K. Kraft. 2021 Bed Bug Handbook: The Complete Guide to Bed Bugs and Their Control 2nd Ed. Pinto & Associates, Inc. Mechanicsville, MD. USA.

Potter, M. F., A. Romero, and K. F. Haynes. 2008. Battling bed bugs in the USA, pp. 401–406. In W. H. Robinson and D. Bajomi (eds.), Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Urban Pests, 3–16 July 2008, Budapest, Hungary. OOK-Press, Weszpreém.

Potter, M. F., K. F. Haynes, J. Fredericks, and M. Henriksen. 2013. Bed bug nation: Are we making any progress? Pestworld (May): 5–11.

Potter, M., J. Fredericks, and M. Henriksen. 2015. Bed bugs across America: the 2015 bed bugs without borders survey. Pestworld (Nov/Dec): 4–14.

Reinhardt, K., and M. T. Siva-Jothy. 2007. Biology of the bed bugs (Cimicidae). Annu. Rev. Entomol. 52: 351–374.

Romero, A., A. M. Sutherland, D. H. Gouge, H. Spafford, S. Nair, et al. 2017. Pest management strategies for bed bugs (Hemiptera: Cimicidae) in multiunit housing: A literature review on field studies. J. Integr. Pest. Manag. 8: 1–10.

Singh N., C. Wang, and R. Cooper. 2015. Effectiveness of a sugar-yeast monitor and a chemical lure for detecting bed bugs. J. Econ. Entomol. 108: 1298–303.

Singh N., C. Wang., C. Zha, R. Cooper, and M. Robson. 2017. Testing a threshold-based bed bug management approach in apartment buildings. Insects 8, 76: doi:10.3390/insects8030076.

Stedfast, M. L., and D. M. Miller. 2014. Development and evaluation of a proactive bed bug (Hemiptera: Cimicidae) suppression program for low-income multi-unit housing facilities. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 5, http://dx.doi.org/10.1603/IPM14003.

Wang, C., and R. Cooper. 2011. Environmentally sound bed bug management solutions. In P. Dhang (ed] Urban pest management: an environmental perspective. CABI International. pp. 44–63.

Wang, C., T. Gibb, G. W. Bennett, and S. McKnight. 2009. Bed bug (Heteroptera: Cimicidae) attraction to pitfall traps baited with carbon dioxide, heat and chemical lure. J. Econ. Entomol. 102: 1580–1585.

Wang, C., K. Saltzmann, E. Chin, G. W. Bennett, and T. Gibb. 2010. Characteristics of Cimex lectularius (Hemiptera: Cimicidae), infestation and dispersal in a high-rise apartment building. J. Econ. Entomol. 103: 172–177.

Wang, C., W. T. Tsai, R. Cooper, and J. White. 2011. Effectiveness of bed bug monitors for detecting and trapping bed bugs in apartments. J. Econ. Entomol. 104: 274–278.

Wang, C., N. Singh, C. Zha, and R. Cooper. 2016. Bed bugs: Prevalence in low-income communities, resident’s reactions and implementation of a low-cost inspection protocol. J. Med. Entomol. 53: 639–646.

Wang, C., A. Eiden, N. Singh, C. Zha, D. Wang, and R. Cooper. 2017. Dynamics of bed bug infestations in three low-income housing communities with various bed bug management programs. Pest Manag. Sci. 74: 1302–1310.

Wang, C., A. Eiden, R. Cooper, C. Zha, and D. Wang. 2019. Effectiveness of building-wide pest management programs for German cockroach and bed bug in high-rise apartment building. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 10: doi:10.1093/jipm/pmz031.

Latest from Pest Control Technology

- Trelona® ATBS in Action

- Cetane Associates Promotes Trey Brasseaux to VP

- Rid-A-Bug Exterminating Celebrates 52 Years in Business

- OSU Research Aims to Pin Down Process of WNV Transmission

- Senske Family of Companies Opens New Headquarters in Dallas

- Washington State Governor Recognizes April as Pest Management Month

- Rose Pest Solutions’ Hozey Graduates from the AGP Program

- 2025 Pest Control Distribution Trends