Mosquitoes cause more human suffering than any other insect in the world. Although mosquito-borne illnesses are kept largely in check in North America thanks to the professional pest management industry and local, state and federal mosquito-control initiatives, it is beneficial to examine and understand the potential of this “rogues gallery” of mosquito-borne illnesses endemic to the United States.

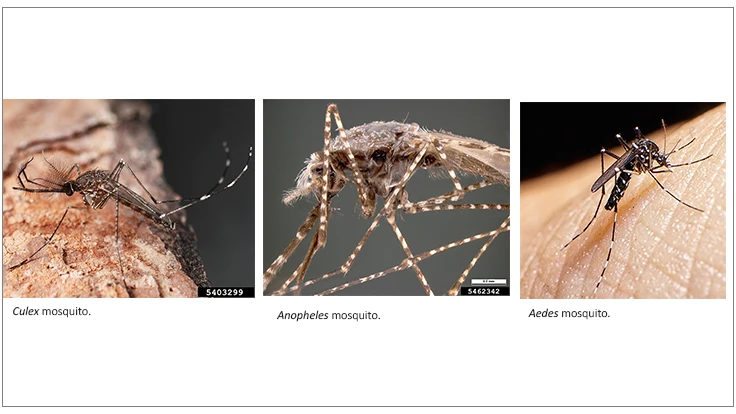

Although all these diseases and conditions are spread by the bite of a mosquito, according to Stan Cope, director of entomology and regulatory services for Terminix and president of the American Mosquito Control Association, PMPs need to understand the differences between individual mosquito species. "There are real differences in the ecology of mosquitoes that determine who gets bit, where and why,” he said. “We need to try to not think about them all as the same.” The common mosquitoes that may transmit diseases in the U.S. include the:

· Anopheles, which spreads human malaria, although this is rare in the U.S.

· Culex, that transmits West Nile virus, encephalitis and bird malaria.

· Aedes, best known currently for its transmission of the Zika virus, though it also can transmit chikungunya, yellow fever and dengue.

Encephalitis. Encephalitis is technically not a disease, rather it is a condition (the severe inflammation of the brain), Cope said. It can occur in the U.S. in a variety of forms including Eastern and Western equine, St. Louis and La Crosse – each of which is different.

· Eastern and Western equine encephalitis are rare diseases in humans – with Eastern equine encephalitis most likely to occur along the Eastern Seaboard and swampy areas and Western equine encephalitis in areas west of the Mississippi River. Although they are called equine, infected mosquitoes also transmit these viruses to people, and birds can carry the diseases. Mosquito-transmitted encephalitis is rare in the U.S., but it is very serious, with half of those who get sick from Eastern equine encephalitis dying and the others possibly being neurologically impaired for life.

· St. Louis encephalitis (and West Nile virus) are most common in urban areas where the mosquitoes live and breed in highly organic and polluted waters, such as storm drains and sewer systems.

· La Crosse encephalitis was discovered in La Crosse, Wis., in the early 1960s but occurs in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeast as well as the upper Midwest. The virus is maintained in nature by small mammals and transmitted by the Aedes mosquitoes that live in and around tree holes – so the disease has been most common in children who climb trees, thus are most likely to come in contact with an infected mosquito.

Although none of these are currently common in the U.S., human efforts will never be able to completely eliminate them because they all have some type of animal reservoir. That is, Cope said, "They can be maintained in nature without any human involvement because they can maintain themselves in animals."

Malaria. Malaria, on the other hand, has been managed more successfully because it does not have an animal reservoir. It needs the human (or higher primate) component to maintain itself, Cope said. So, although there are mosquitoes in the U.S. that can carry the parasite, the disease has to be introduced by infected humans. It could then be passed through a mosquito, which bites an infected person, and then later bites others.

Zika, Chikungunya, Yellow Fever. Although these diseases are not the same, the mosquito vector is. Like malaria, these diseases have no other animal reservoir other than primates, so they would not be introduced into the U.S. except through infected travelers. That is, if a person were to be infected during his/her travels in Zika virus areas, then travel to the U.S., then be bitten by an Aedes mosquito – that mosquito would become infected. It then takes 10 days to two weeks for the virus to multiply in the mosquito’s body and enable transmission, but anyone bitten by this mosquito after that time (assuming it lives that long) would likely become infected.

Dog Heartworm. The name of this disease is a misnomer. Although dogs and raccoon are the most commonly infected, other animals, including cats, as well as people, also can contract heartworm. In addition, the disease is so widespread because it can be carried and transmitted by more than 70 mosquito species, which are found in most parts of the U.S.

When the infected female mosquito bites the animal, it deposits infective larvae onto the animal's skin, which then enter the new host through the mosquito’s bite wound. In some areas, Cope said, there is a nearly 100% risk that an outdoor dog will get this serious and potentially fatal disease if a preventive medicine is not administered.

Other Factors of Transmission. When discussing the potential of mosquito-borne disease and its control and prevention, the flight range of the species must also be considered. The Aedes aegypti mosquito (which transmits Zika) breeds in artificial containers containing water and generally stays within 100 yards of its breeding site – and goes that far only if needed for survival resources, Cope explained. On the other hand, the Culex and Anopheles will fly up to a mile and a half or more. Additionally, while most people associate mosquito bites with the time period of dusk to dawn, some mosquitoes – such as the Aedes aegypti – are also active and bite during the day. Such information is critical in developing a successful control program.

Latest from Pest Control Technology

- Cavanagh Explores Termite Mounds on Recent African Safari

- Deer Mouse and White-Footed Mouse Q&A

- Massey Services Gives Back to Several Organizations Over Holiday Season

- The Power of Clarity at Work: How Goals, Roles and Tasks Transform Teams

- Unusual Pests of New Homes

- 2024 Crown Leadership Award Winner Bill Welsh

- UC Riverside Scientists Study New Termite Treatment Methods

- Lindsay Hartnett Honored with First Annual Eco Serve HEARTS Award